The Making of the New Town

By Paul Sherry

Blight or Bounty for the communities of East Shropshire?

The New Town has, since its earliest origins, always prompted robust debate, especially in the older settlements which surround the Wrekin. Variously viewed as a massive land reclamation project and overspill town for the second city, major social engineering project or futuristic 21st century town; Telford has already created its own history. As the initial focal point Dawley New Town, as it was first known, was at the centre of the discussions. Councillor George Chetwood had lived in the area all his life and had seen for some time the effects of mine workings and the old factories. In 1946 he joined Dawley Urban District Council (UDC) and vowed to get something done about the ‘derelict mess’ the district had become.

So how and why did the New Town come about?

In the 19th century and with the coming of the Industrial Revolution, Britain changed from being predominantly rural to mainly urban. Concentrated industrialisation led to overcrowded, insanitary working and living conditions surrounded by scarred and polluted landscapes. The eventual government response was two major pieces of legislation: New public health, Town Planning and Housing Acts and The New Towns Act of 1946. The arrival of the legislation stimulated a wave of regeneration and reclamation in the areas which had felt the worst effects of the rapid shift to mechanised production.

The big news for UDC came in June 1962 when the Minister of Housing Dr Charles Hill announced that a new town would be built in the area to relieve congestion in Birmingham. He believed that a satisfactory new town could be built at Dawley to include, ultimately, a population of 80 – 90,000 of whom he hoped 50,000 would come from Birmingham.

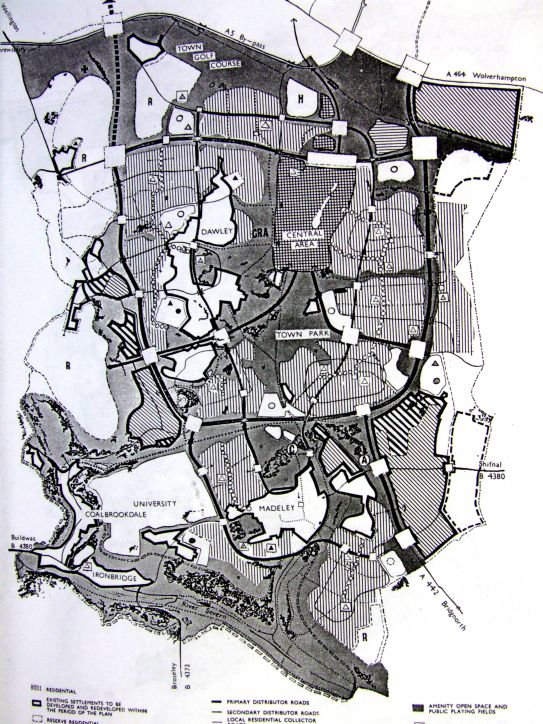

The slow, natural almost ‘organic’ growth of the Dawley area would be replaced by rapid, ‘zoned’ and centrally planned development. The task ahead was a daunting one, even for an organisation as well resourced as the Development Corporation. Vast swathes of derelict land needed to be treated before anyone could begin to envisage the new city of the future to be built in its place.

The statistics at the time were quite staggering:

- 5230 acres of derelict land, scarred by years of intensive mining and industrial activity

- 2820 acres of land covered by spoil and waste deposits

- 2957 recorded abandoned mineshafts and adits

- 830 acres of disused quarries and opencast mines

- 120 miles of abandoned canals and railways

- 3730 acres of underground shallow mineral working

- 7140 acres affected by past subsidence from abandoned deep mine workings

This same landscape had also played an important role in leisure activities for many generations. Even into the early years of the twentieth century there were many hidden places amongst the pit mounds which were venues for bareknuckle fighting between the men of the settlements. Football and cricket were also played there in later years.

The government announcement generated ripples of excitement as visions of the new city of Dawley New Town began to emerge.

But there were also tensions and fears of the unknown

In this close knit traditional mining there were concerns about the possible negative effects of the plans. Worries too about seismic changes to living and working patterns developed over centuries which would now inevitably change forever. Battle lines were being drawn. The local authorities of Dawley, Oakengates, Madeley and Wellington and subsequently Wrekin Council were immediately pitched into discussions at the highest level which would decide the fate of their communities.

However, the choice of Dawley had come as no surprise to many local residents. As far back as 1952 Dawley UDC prepared a scheme to deal with reclamation of 30 acres of pit mounds for housing but it was found that the town did not have the financial resources for a project of this scale. But the idea that Dawley could help with Birmingham’s overspill problem was first suggested in an article published in the Birmingham Gazette in 1955 headed ‘Here’s a place for overspill’ by the Wellington Journal correspondent Mr A. W. Bowdler stating, ‘the once famous industrial areas of Shropshire could be brought back into prosperity again, giving great help to the overspill problem.’ Following on from the article, Cllr George Chetwood (by now Chairman of Dawley UDC) sent a letter was sent to the Lord Mayor of Birmingham offering UDC help and support. The letter stated ‘It should be possible to incorporate a town of more than 100,000 people. The area is sufficiently far from Birmingham to prevent adding to the city’s congestion but close enough not to destroy all links with the city.’ This led in turn to visits to Dawley and Birmingham by both parties and the start of a long period of negotiation and technical discussions.

Against this background the discussions began

Cllr. George Chetwood, known as ‘Mr Dawley’ and widely recognised as the ‘father’ of the Council, having served as a member for over 25 years, was to become an important advocate for the community in the sometimes heated discussions with the Development Corporation.

He took issue at an early stage with the Development Corporation’s housing policy claiming that it had stifled the Council’s own development in favour of its own plans. This he said had led to many people relocating to Oakengates and Wellington where the local Councils were still able to build new homes without restriction.

Compulsory purchase of land and property in Dawley and elsewhere brought mixed fortunes. Tenants were paid normal compensation for tenant’s rights and disturbance, and could be offered discretionary payments of up to two years’ profits for some businesses. Owner occupiers were paid the vacant possession value of their property and received only legal and removal expenses. Although some people declared themselves reasonably satisfied with the terms offered, others were unhappy and claimed that the compulsory purchase of sound properties as well as slums was forcing relocation and consequently the break up or indeed destruction of old established communities. The hamlet of Dark Lane had to be demolished and its inhabitants were promised by the Development Corporation that they would go into better housing not too far away and it tried to house them as a community. However the first twelve families were moved to Oakengates. This action worried the people of Old Park whose land was to be used in a future phase of development. This old community could remember a time when it could support a village school, a chapel and a sprinkling of village shops. Many local people were upset by the impact of these actions on old established settlements and some resentment remains even to this day.

Shirley Tart, in an article for the Shropshire Magazine, captured the emotional turbulence as villages and hamlets disappeared. For several generations cosy, intimate, self-contained communities such as Dark Lane had been little disturbed by the outside world. ‘my maternal grandmother lived in a cottage which had only ever been inhabited by members of my mum’s family, while dad’s mother and sisters lived at right angles, farther down the track’

Idyllic scenes of bulrushes, tadpoling and tree climbing, ‘gleaming gorse’, ‘mountains which were really pit mounds’ are contrasted with devastation as the little 19th century village of Dark Lane was reduced to ‘a replica of a massive and grotesque bomb site’.

As part of the planning process vast acreages of virgin pasture, open fields, farms and smallholdings were bought up by the Corporation in preparation for development. Much resentment remains to this day on the price paid under compulsory purchase arrangements. Affected families point to huge profits generated as land was sold on to developers and a number took their claims to the high court and beyond to secure a better deal. Any profits helped finance the costs of road, services and land reclamation.

Many people still have vivid memories of the rural nature of areas which have since changed beyond recognition; gently undulating pastures around old Stirchley village turned over to housing, education and recreation facilities, farmland at Dark Lane and Priorslee to the courts, police station and cinema at the Town Centre and prime agricultural land at Hortonwood to Industrial estates.

The macro-planning of infrastructure on a massive scale – roads, sewers and industrial and housing estates - did not allow for the survival of older settlements and where they did survive it was often in name only - ‘every homestead, allotment, each down-the-garden privy wash house, all the grandly customised sheds were crushed between bulldozer and earth remover’ ‘it was felt that homes, lives and a solid and enduring community were also being crushed and broken. It was the end’

The scale of the settlements which fell within the new town remit can be gauged from records. ‘A History of the County of Shropshire’ notes that Hinkshay had a ‘double row’ of 48 back to back cottages and a ‘single row’ of 21 houses, Dark Lane over 60 cottages in three long terraces and Horsehay’s former potteries had been converted into 24 separate dwellings. These communities also contained extensive garden allotments and many rented and unfenced plots. The majority had been cleared away by the mid 1970s.

Inevitably, the impact on some of the established communities was drastic – some good housing stock as well as substandard was knocked down, some communities were destroyed completely – the villages of Dark Lane and Hinkshay disappeared from the map; families were relocated to unfamiliar areas.

The social upheaval of New Town planning was not foreseen by inhabitants and the vision of a 21st century city did not compensate them for their loss.

The impact of the new town was beginning to bite deeply into the old culture

The impact of the new town was beginning to bite deeply into the old culture

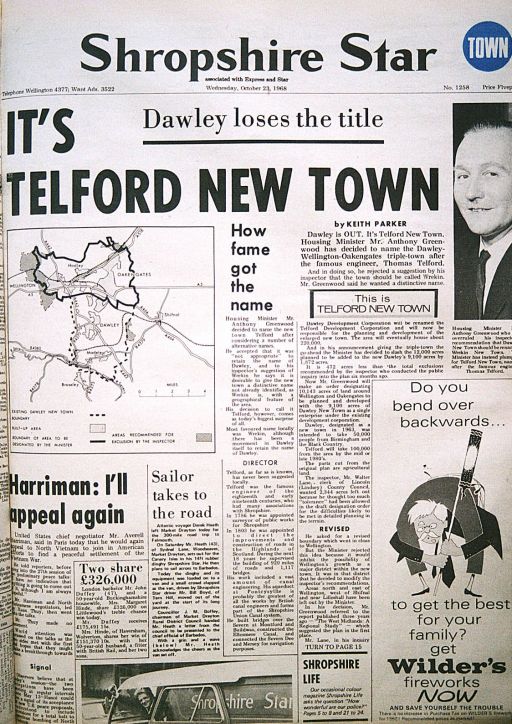

About this time the name of the New Town was already being questioned. Dawley was the only local authority wholly within the designated New Town boundary and the working name made great sense. However, in 1968, and despite strong resistance from Dawley Council and local residents, the name was changed to Telford by the then Housing Minister Richard Crossman.

Locally the name ‘Wrekin’ was rejected in favour of the name of the famous engineer who in 1786 was appointed as Shropshire Surveyor of Public Works and who built many local landmarks.

Meanwhile Bill Yates, the sitting MP and an ardent supporter of the New Town memorably declared it would be the ‘setting for the second industrial revolution’

Further support came from the Clerk to Salop County Council said that they ‘welcomed the New Town announcement and although the County would have a lot of expense it would be a good investment in the long run’

Throughout, the Dawley Observer continued to record the thoughts of the few individuals who were convinced that Dawley could be restored to its former industrial greatness.

But the task of creating the town was not given to locally elected democratic bodies. Instead teams of Planners, Engineers, Architects, Surveyors needed to build a town from scratch were recruited. The steering body for this huge project, the Development Corporation, was appointed by central government and was made up of a variety of public and private sector representatives.

The size of the task facing the planners of the new city should not be underestimated. In a nutshell, the challenge would be to overlay and integrate a new settlement designed for the next 200 years with its entire accompanying infrastructure onto old communities developed over centuries with their equivalent housing and transport networks.

To change a community’s way of life in this way required both radical and robust thinking but also the utmost tact and diplomacy in the debate to come. However the town was planned, the impact for good or bad would be significant.

So did the reality match the vision, has the New Town delivered all that was promised and did Dawley lose or gain from it all?

It may be too early to answer these questions; after all Telford hasn’t yet reached its half century and in a constantly evolving environment perhaps a longer perspective is needed - perhaps a hundred years or more.

When is a town considered to have reached maturity?

A look back to earlier days may help the discussion.

At New Town designation Dawley’s industrial strength had been in decline for some time. 100 years of rapid growth and prosperity brought the description to the whole area of ‘the most important industrial area in the world.’ However a long slow decline followed over the next century. Coal mines and foundries could no longer compete, unemployment was at a record high, poverty increased and the legacy for the environment was dramatic – a moonscape of pit mounds and dereliction; a scene outsiders may have regarded as a true wasteland as they passed through on the train or by car but containing a strong sense of community and heritage which exists to this day.

By 1964 the community was hugely dependent on manufacturing. More than 78% of workers were employed in this sector compared with only 44% in Britain as a whole. The spectre of unemployment was already looming as traditional industries began to close. Because of this dependency the Dawley area was always destined to suffer more than most.

The Birmingham end was at the same time going through its own severe problems with substandard housing, inner city congestion and decay leading to poor quality of life and poverty.

It became clear to the Development Corporation that if it was to achieve its aim of creating a self-contained and balanced community it would be necessary to broaden its economic base. This would guard against major structural unemployment if one or two sectors of the economy were to go down.

The big breakthrough came with the attraction of the first Japanese company, Maxell, in 1983. 130 further overseas companies quickly followed. Thereafter a number of key events really put Telford on the map:

1973 – Phase 1 of Telford Town Centre opened

1981 – Phase 2 of Telford Town Centre opened

1983 – M54 linked to M6

1986 – Telford railway station opened

1987 – M&S into phase 3 of Town Centre

1989 – Telford Hospital opened

1990 – Telford campus of Wolverhampton Polytechnic opened

What of Dawley today? Has it suffered from the presence of the new town on its doorstep?

To an extent all of Telford’s Borough Towns – Wellington, Ironbridge, Madeley, Oakengates and Dawley have been affected but the debate must be viewed in the context of the national situation. Throughout the country, changing shopping patterns with greater use of out of town shopping centres and use of the internet have, with some notable exceptions, hastened the steady demise of market towns. Traditional shopping may be in decline - never to return – which begs the question about the future of the High Street in general.

In Dawley’s case there is debate about whether it has suffered disproportionately with the additional threat of having a major regional shopping attraction on its doorstep. However, it has also been suggested that this proximity could in time be turned to advantage. As the closest of Telford’s Borough Towns to the shopping centre, it is already beginning to position itself in a new market. It has much to offer as an older community with a rich heritage of mining and traditional industry – a time capsule of a community with close links to the past and all within walking distance of Telford centre.

Within 50 years we may have come full circle so that the legacy of Dawley’s prosperous and dynamic industrial heritage will be a foundation for a strategy to take it through to the next millennium.

References

Mr A.W. Bowdler, originally printed in Birmingham Gazette, Feb 1955, quoted in Wellington Journal and

Shrewsbury News, June 1962

Mr Charles Savage, Dawley Surveyor. Letter to Birmingham Gazette, Dec 1955, printed in Wellington Journal and Shrewsbury News, June 1962

S. Tart, Shropshire Magazine, October 2009

Mr G.C. Godber, Clerk to Shropshire County Council. June 1962, Wellington Journal and Shropshire News

Bibliography

M. De Soissons, (1991). Telford, The Making of Shropshire’s New Town, Shrewsbury, Swan Hill Press

G. C. Baugh, (1985). Victoria County History: Shropshire, Vol. 11

Photographs

1 Map of Telford New Town showing mine workings

2 Shropshire Star Article, “It’s Telford New Town” 23.10.1968. Reproduced courtesy of the Shropshire Star

3 Masterplan for Dawley, Dawley Observer on 22.01.1965. Reproduced courtesy of the Shropshire Star

4 Photos of Telford reproduced courtesy of Richard Byfield