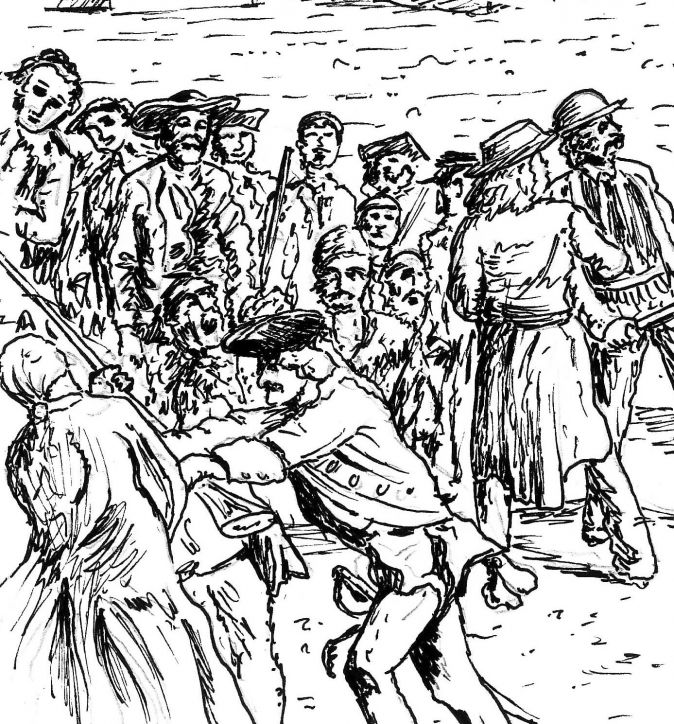

Battle of Cinderloo by P. Sherry

BATTLE OF CINDERLOO

Workers’ Revolt in Cinderhills at Old Park

By Paul Sherry

Waterloo, Peterloo…major events in British history which immediately bring to mind images of violence, loss of life, hardship and also reminders of turbulent times in domestic life, political and economic change, social reform and religious revival.

Waterloo, Peterloo…major events in British history which immediately bring to mind images of violence, loss of life, hardship and also reminders of turbulent times in domestic life, political and economic change, social reform and religious revival.

But what of Cinderloo? The name has echoes of the well documented events of the early 1800s which impacted on the whole nation, but how much did this less well known East Shropshire uprising impinge on national consciousness and did it also play a part in helping to shape the great political, social and economic movements of the time?

Cinderloo: the name links Dawley and the locality inextricably with the two bloody confrontations and immediately gives clues to how events unfolded on the day. Like Peterloo, causes and effects revolved around the major issues of the time; a period of severe distress and discontent with the ‘monster of national debt’ following the Napoleonic wars, and the new Corn Laws as the backdrop to dissent which brought the country to the brink of the real danger of a possible French-style revolution.

The simple facts of what is now known as ‘The Battle of Cinderloo’ are that on February 2nd 1821 more than 500 miners gathered in Dawley and marched in protest at pay cuts and increasing poverty. The march gathered in numbers and force, more than 3,000 at its height, and culminated in a pitch battle with the local Yeomanry which left two miners dead, many injuries on both sides and a lasting bitterness and anger amongst working people in the East Shropshire Coalfield.

To begin to understand how the country came so close to a national uprising it is important to look behind the bare facts and into the background, the mood of the nation, the impact of economic policy and political turbulence on workers and families and how this gave rise to anger, protest and ultimately tragic consequences.

The Duke of Wellington’s famous defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 was a much celebrated victory but the aftermath was a very different story for England. The economy, which in wartime had created employment and flourished in supporting the needs of the army for weaponry, equipment and uniforms, was plunged into stagnation. Unemployment and the fears associated with it began to dominate thinking in the workforce of both the newly industrialised areas and the rural communities.

During the early years of the nineteenth century, the East Shropshire Coalfield including Oakengates, Ironbridge, Coalbrookdale and the Dawley area reached its peak. Dawley as a community developed over shallow coal measures which were easily workable and there were productive coal seams to be mined between Old Park and Heath Hill and further south at Lightmoor. Further east and north the seams were deeper and the coal less accessible.

The Napoleonic Wars had seen the rise of new industrial areas – Birmingham and the Black Country, the South Wales Coalfield and the textile areas of Lancashire and Yorkshire. They were built and developed on the achievements of the early years of the industrial revolution and its pioneer entrepreneurs but had the added advantage of being located in more accessible areas with better transport links across the country, enabling raw materials and finished goods to be moved more quickly and easily. These areas would eventually overtake the East Shropshire Coalfield which, by the 1840s was already beginning its long decline.

The depressed state of the of the national economy, particularly the iron trade from 1815, caused great hardship which was made worse by the passing of the Corn Laws in that same year. This increased the price of bread and basic foods and caused much resentment amongst workers who were already faced with increasing oppression from employers.

Throughout the Industrial Revolution the price of bread was seen by the people as the yardstick of living standards and when the Corn Laws were passed the Houses of Parliament had to be defended from the public by troops.

This period of chronic economic depression was particularly felt by textile weavers and spinners in the north of England. Weavers, who could have expected to earn 15 shillings for a six-day week in 1803, saw their wages dramatically cut to 5 shillings or even 4s 6d by 1818.The Corn Laws, the first of which was passed in 1815, imposed a tax on foreign grain in an effort to protect English grain producers. The cost of food rose and people were forced to buy the more expensive and lower quality British grain. Periods of famine and chronic unemployment ensued, fuelling the desire for political reform both locally and throughout the rest of the country.

The gathering mood of confrontation and the potential for revolution showed itself in June 1817 when workers in different parts of the country demonstrated against the conditions they were having to endure.

By the beginning of 1819, the poverty experienced by the cotton loom weavers of south Lancashire was such that they had reached crisis point and were ready to be influenced to publically demonstrate their feelings by the more radical thinkers and activists of the time as well as leaders from their own communities. A "great assembly" was organised by the Manchester Patriotic Union, a group agitating for parliamentary reform. The secretary of the union, Joseph Johnson, wrote to the well-known radical orator Henry Hunt asking him to chair a large meeting planned for Manchester on 2 August 1819. In his letter Johnson wrote:

‘Nothing but ruin and starvation stare one in the face [in the streets of Manchester and the surrounding towns], the state of this district is truly dreadful, and I believe nothing but the greatest exertions can prevent an insurrection. Oh, that you in London were prepared for it.’

A public reform meeting was called, to be held on the 16th August 1819 in St Peters Fields, (now known St. Peter’s Street) as there was no building thought big enough to hold the anticipated crowd. Henry Hunt was to address the Meeting. Estimates put the crowd at variously 30,000 and 150,000 people - in any case, we can be certain that there were more people present than Manchester had ever seen in one place before. Disturbed by such large crowds, magistrates called in local militia to stand ready.

Some 1500 troops assembled, comprising the 15th Hussars (professional soldiers) and soldiers of the Manchester and Cheshire Yeomen Cavalry (a largely volunteer force), commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Guy L'Estrange. Magistrates, fearing insurrection and riots, ordered Hunt and other leaders to be arrested before they could speak, though the meeting had been thus-far peaceful and orderly. Inadvertently a mounted soldier brushed and knocked down a mother, killing the child she was carrying, and panic ensued.

Magistrates, and the troop commander, misread what appeared to be a riotous outbreak, and ordered Yeomanry, who were standing ready just off Portland Street, to go in to break up the affray.The armed cavalry sabres drawn, charged the crowd, cutting people down indiscriminately. Men, women and children were hacked down or trampled by horses or people in flight. After ten minutes of havoc and slaughter, the field was deserted except for the broken hustings platform, bodies of the dead, wounded and dying. 15 people were killed and 400–700 were injured. The massacre was given the name Peterloo in ironic comparison to the Battle of Waterloo, which had taken place four years earlier.

It was against this background of dissent and unrest that Dawley’s historic events took place. The first signs of trouble came in June 1820 when mineworkers’ employers attempted a savage cut in wages. This they said was due to a decline in the value of iron and a general stagnation of trade. The miners came out in protest, did some damage to property and eventually met in conflict with the local Shropshire Yeomanry. Fortunately casualties from the battle which followed were minimal with only one miner wounded; but critically the employers backed down and the Yeomanry persuaded the strikers to accept arbitration by a board made up of local landowners and a clergyman. The board’s decision was that the men were entitled to their current level of wages and the strike was called off.

However, stability was not to last long and the following year employers made it clear that they would be reducing wages by 6 pence a day from the average wage of 15 shillings a week - for the same reasons they had given the previous year.

A letter sent to Lord Sidmouth at the Home Office by local magistrates encapsulated the authorities’ underlying worries of rebellion and revolution. The letter requested military support for the local Yeomanry, which it was thought, would not be able to put down an uprising. As it turned out the letter arrived too late to have any bearing on subsequent events.

On February 1st colliers went on strike and enlisted support at ironworks in Ketley, New Hadley and Wombridge where production was successfully halted. On the following day, striking colliers, many armed with sticks, left Donnington Wood to remove the plugs from furnaces at Old Park Ironworks, their numbers swelling as they went. From Old Park, they continued onto the ironworks at Lightmoor, then those at Dawley Castle and Horsehay with the intention of ending their march at Coalbrookdale. However, by the time they had reached Horsehay, news of their actions had led to the Shropshire Yeomanry and Special Constables being summoned. Instead of continuing their journey south, they started to return north and by 3 O’clock that afternoon their numbers had swelled to over 4,000 and the crowd included women and children. The Yeomanry and constables caught up with the strikers as they gathered near the ironworks of Messrs. Botfield on the steep slopes of the slag heaps, known locally as the cinder hills. These vast man-made constructions had been accumulating over perhapstwenty to thirty years and consisted of production waste from the furnaces.

It is worth recalling that no regular police force existed at the time and law enforcement was left to beadles, special constables and watchmen. However, their numbers were very small indeed compared to population size. In Manchester for example, with 187,000 residents, the police force consisted of just 4 beadles, 53 night watchmen and 200 special constables. The Yeomanry was the only alternative. Although the army had been used before in similar cases, the nation’s collective memory of events at Peterloo was very strong, and this was now regarded as a last resort by the government. The government did however champion the retained body of ‘Yeomen’. Drawn from farming, manufacturing and merchant classes they were seen as supportive and reliable in this situation especially as their officers came from landed gentry and property owners. By contrast the Militia, a volunteer force made up of ordinary working people maintained by the government during the Napoleonic threat, was disbanded because they had on many occasions taken the side of the rioting groups they should have been helping to control.

The crowd, who had armed themselves with a variety of weapons, sticks, bludgeons and of course the raw materials of the cinderhills themselves had the temporary advantage of elevation and were behaving in an agitated and threatening manner. The Riot Act was read by Thomas Eyton, one of the magistrates, and the crowd was given one hour to disperse. This failed to have any effect. Instead, the crowd became more violent with shouts of “If we are to fight for it; let’s all get together”, and “We will have our wages.”

An hour later, Colonel Cludde, who was leading the Yeomanry, gave the order for the cavalry to advance to begin the process of breaking up the crowd. He also ordered the Peace Officers to take the ringleaders and any rowdy protesters into custody. It was at this point that the conflict came to a head. Two men had been arrested by the Constables. The attempt to begin transporting the arrested men to the lock-up at Wellington was the catalyst for violence as the colliers on the cinder hills nearest the road rained down stones, heavy lumps of slag and anything else which came to hand onto the troops below. A striker called Thomas Palin then successfully led a group to free the arrested strikers. It was this act which seemed to create panic in the ranks of the Yeomanry, who were unable to ascend the steep and treacherous cinder hills. Colonel Cludde ordered them to open fire.

The consequences were serious. One miner, William Bird, aged eighteen was killed outright and another, Thomas Gittins, was mortally wounded. Thomas Palin who led the attacking group also received a gunshot wound as did several other strikers and spectators. Although it was said that many of the Yeomanry were also injured from flying debris from the cinder hills it seemed from later testaments that the majority of wounds were insignificant.

An inquest into the men’s deaths was held on 6th February. The jury returned verdicts of justifiable homicide. A number of arrests were made in the days and weeks that followed and nine of the prisoners, Thomas Palin, Christopher North, John Payne, James Eccleshall, John Grainger, Samuel Hayward, Robert Wheeler, John Amies and John Wilcox were tried before Salop Assizes on March 25th 1821. Thomas Palin was tried for the capital crime of felonious riot and was hanged on 7th April. Samuel Hayward was also sentenced to death but was reprieved on 2nd April. The remaining men were found guilty of riot and were imprisoned for nine months.

‘The reprieve of S. Hayward, under sentence of Death for riot &c. at Wellington, was received on Monday. T. Palin remains for execution and manifests great contrition. We are requested to contradict a published report which has made a painful impression upon the mind of this unfortunate man and his friends, viz, “that his grand-father was executed for a similar offence.” The grand-father of Palin is now living with a son, at Lilleshall-Hill near Newport; and the grand-father of Mrs Palin (T.Adderley) resides at Madeley Wood.

By contrast Colonel Cludde received a letter from the government congratulating the Shropshire Yeomanry on the way they dealt with the incident at Cinderloo. The letter was however cautious in tone following the equivalent letter sent to the Cheshire Yeomanry following the Peterloo demonstration. At that time there was a public outcry about the perceived insensitivity of the government sending a letter which gave unequivocal and enthusiastic approval to the actions of the Yeomanry for their part in an incident which led to so many deaths and injuries.

After Peterloo the then Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, conveyed to the magistrates of Manchester the thanks of the Prince Regent for their action in the "preservation of the public peace". That public exoneration was met with fierce anger and criticism.For a few months following Peterloo it seemed to the authorities that the country was heading towards an armed rebellion.

The letter to Shropshire, however, from Lord Sidmouth, to the Earl of Powis, Lord Lieutenant of Shropshire struck a different note referring to ‘the patience with which the Yeoman Cavalry bore the insults of the rioters, of the caution and circumspection used by the Officers before the men were permitted to act offensively, and of their exemplary forebearance till the moment when they were at length unfortunately obliged to have recourse to arms’ These sentiments were slightly tempered by Lord Sidmouth’s ‘great regret that I learnt the melancholy consequences which ensued, but it is some consolation to have ascertained that those who fell were among the ringleaders of the riot, and it is satisfactory to learn that the juries who sat upon the inquests were convinced that the homicides were fully justified by the circumstances.’

The effect on the local mining community was felt for many months. Damage to mining equipment during the riot meant that miners had to be laid off, adding to the conditions of poverty and hardship they were fighting against.

Although the majority of ironmasters carried out the threat to reduce wages by 6d a day, some of those in the south of the area, including the Botfields and the Lilleshall Company did reach a compromise and agreed a reduction of 4d a day.

Overall the riot left workers disillusioned and broken in spirit and, in the majority of cases, in worse circumstances than before. Cinderloo also left a mood of unease amongst employers, magistrates and others who made up the ruling class at the time, who feared an organised, revolutionary uprising. However, although the prevailing undercurrent in the country was of rising discontent, it seems that the Cinderloo incident was not part of any cohesive movement but stands alone as a desperate act of expression driven by frustration and truly terrible working and living conditions.

Although there were no significant links to the national movements for political reform at the time, the incident at Cinderloo does show the turbulence of class struggle and the general direction of travel for the working class in eventually bringing about changes in working life. Defeat at Cinderloo had a demoralising effect on the workers of Dawley and district and their families. This was indeed a major event in their lives which did nothing to improve relationships with employers and led to a downturn in fortunes and general disillusion. The rise of religious revivalism in the area at this time may or may not have been linked to the tragic events in the cinderhills at Old Park but it is clear that people were looking for new certainties in a world of fragile economics and failing politics.

People had experienced many years of hardship and poverty and their attempts at agitation and protest had been quickly and efficiently put down. In this environment Methodist preachers found a ready audience desperate for somewhere to turn to Methodism in its various forms became the established religion of the coalfields during the nineteenth century with Madeley being regarded as the ‘Mecca of Methodism’. Following Cinderloo, there were significant increases in Wesleyan membership in both the Wellington and Madeley circuits with the Wesleyan Methodist Magazine reporting in April 1821 ‘everywhere there is a thirst for the Word of Life’ Indeed in the month of Thomas Palin’s execution revivalist missionaries from the Potteries attracted large audiences from men employed in pits and ironworks around Wrockwardine Wood, Oakengates and Dawley and it is easy to make a connection with the tragedy at Cinderloo and its after effects. It has been suggested that the religious revival which became prominent in the coalfield after Cinderloo may have served a double purpose - as an aid to employers and landowners in suppressing and reducing potential for uprising; and for workers as a comfort in troubled times. Cinderloo, like many demonstrations and disturbances of the time, was an expression of frustration at the hardship and poverty of the economic conditions being experienced by working people, in this instance those in the East Shropshire coalfield at a time of rapid change and mass industrialisation.

In this relatively small industrial area it had as profound an effect on local people as Peterloo had had in the Manchester area. Like Peterloo, it was sufficiently alarming to become of significant importance to national government, as the letters from the Home Office to Colonel Cludde clearly show. Cinderloo, along with the other demonstrations of industrial social unrest, served to show that people were willing to fight for better living and working conditions.

Cinderloo alone did not seem to have had any great effect on the speed of reform, but it was certainly integral to the movement of working people demanding reform which eventually forced the government of the day to recognise the need to change by passing the Great Reform Act of 1832 which gave way to a period of political, social and industrial reforms which continued well into the 20th century and indeed shaped modern Britain.

In 1846, bowing to public pressure, Sir Robert Peel repealed the much hated and feared Corn Laws of 1815 which had brought about so much social and industrial unrest. The coming of free trade meant that the working classes had access to better and cheaper food and the health and welfare of the population gradually improved as a result with the advent of new programmes of social welfare and political reforms throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

At a local level the overall pattern of industrial life in the East Shropshire Coalfield became one of long slow decline up to the 1960s, notwithstanding some periods of renewed prosperity created by a number of local industrialists who were well placed to respond to new industrial needs as they arose. In the Dawley area they faced the new challenge of industrial and social survival as the mining and heavy industry in the area played out. In a bid to reverse the trend, Dawley Urban District Council approached the government of the day to create Dawley New Town to cater for the Birmingham overspill and regenerate the area. This ultimately led to the founding of Telford as we know it today.

Dawley has faced many challenges in the past and now finds itself economically at a crossroads once more. There is much in Cinderloo which tells us about the indomitable spirit of Dawley people when faced with challenge and adversity. It is this spirit which is still prevalent in the local community that will enable Dawley to begin a new phase of its history.

Written with advice and support from Pam Bradburn DL

Further reading:

Baugh, C.G. (Ed) The Victoria County History of Shropshire, Vol XI Telford – Gloucester, OUP

Briggs, A (1979) Ironbridge to Crystal Palace – Impact and images of the Industrial Revolution, London, Thames & Hudson Ltd

De Soissons, M. (1991). Telford, The Making of Shropshire’s New Town, Shrewsbury, Swan Hill Press

Gladstone, E.W (1953) The Shropshire Yeomanry - 1795-1945, Manchester, Whitethorn Press

Morgan, K.O. (1984) The Oxford Illustrated History of Britain , London, OUP(10)

Thomas, I. ( ) Cinderloo – Riot, Repression and Revivalism in the East Shropshire Coalfield, Phd thesis.

Trinder, B. A (1983) History of Shropshire, Phillimore & Co. Ltd. Chichester